Bassoe

Well-known member

source

If you want to understand where the US-Russia relationship went off the rails, I think you should start with House of Cards, Season 3, Episode 6, which aired in 2015. Bear with me (spoilers coming in the next three paragraphs).

I stopped watching House of Cards at the end of Season 4, so I don’t know what happened after that, although I know Kevin Spacey was canceled and dropped from the series. For those who haven’t seen it, the show in its early seasons starred Spacey as Frank Underwood, one of the last of the white Democratic congressmen from the South, and featured his rise to the presidency.

By the time of S3:E6, Underwood has reached the top job and basically solved the problem of Middle East peace through negotiations with Russian President “Viktor Petrov”, an obvious stand-in for Putin. Everything has been worked out, except for one pesky detail. The homophobic Russians have arrested Michael Corrigan (John Pasternak), an American gay rights activist, and won’t let him go until he apologizes for being so gay in front of children. The whole deal rests on this, otherwise the Russians won’t go along. Putin reveals he has two cabinet ministers who are gay, and his ex-wife’s nephew who is like a son to him is also gay, but despite all this he must take into account the feelings of the Russian people and can’t budge on the LGBT issue (this reassures the viewer that no intelligent person can disagree with them, only dumb rubes). Underwood doesn’t really care about this, but his wife Claire (Robin Wright) does, and she meets Corrigan in his prison cell, where she comes to sympathize with the activist as he refuses to agree to the conditions of the release and demands that Putin accept his gayness instead. Claire takes his side against Frank and Putin. I won’t spoil the ending for those who care, as it’s not relevant to appreciating the importance of the episode.

There are two things to understand about House of Cards. First of all, it is a show made for people who are very into politics, highly educated types whose views are shaped by what’s in The New York Times and The Atlantic. In other words, liberals who get caught up in mainstream hysterias like Russiagate, but who are not so angry or far out there that they are on the cutting edge of wokeness and can’t appreciate an artistic portrayal of the highest levels of American politics. Second, the theme of the show in its early seasons was that Frank and Claire are ruthless political operators who will crush anyone in their path in pursuit of power. Claire was willing to blow up a Middle East peace deal and perhaps her husband’s chances for reelection out of a genuine concern for a gay rights activist, a rare instance of idealism in a show known for having such a cynical take on American politics that it has been promoted by geopolitical rivals. Sure, the Underwoods are monsters, but not even Claire can deny the moral strength of LGBT as a geopolitical issue. To the show’s audience, stopping Arabs and Jews from killing each other pales in importance.

The background of this is that in 2013, Russia passed a law banning gay propaganda towards minors. This came on the heels of the 2012 arrest of members of Pussy Riot, a female performance art collective, for sacrilegious acts at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow. Three members of the group were sentenced to two years in prison each, with two of them serving their full sentences, and upon release they would face off against Putin in Season 3, Episode 3 of House of Cards.

The US response in the media to Pussy Riot and the anti-gay law was nothing short of hysterical, and coverage of Russia, a country that had previously been viewed largely with indifference by American elites, has never been the same. My impression is that the gay propaganda law may have gotten more coverage in the American press than any other event that happened in Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union.

In the 2012 election, when Romney called Russia “our greatest geopolitical foe,” Obama famously responded that the 1980s called and it wanted its foreign policy back. This was before the gay propaganda law. Although it’s hard to prove that this was the turning point, as someone who was studying international relations at the time on a university campus and who paid close attention to American politics, it felt as if some Rubicon had been crossed and any move towards friendlier relations was impossible. By 2015, even before the rise of Trump, Putin was not the leader of a country, but a Hollywood villain.

In 2014, we saw the overthrow of Yanukovych, the Russian seizure of Crimea, and the beginning of the war in Eastern Ukraine. While this was a big deal to foreign policy hawks, it did not capture the liberal imagination in the same way that the gay propaganda law did. Russiagate required years of demonization in order to take off, and beginning in 2016 Putin became not only a homophobe and anti-feminist, but the man who may ultimately end American democracy.

Is LGBT that Important?

I think most people are going to be inherently skeptical of the idea that LGBT and identity politics more generally play such a large role in international affairs. Yet people have less trouble accepting the fact that largely symbolic culture war issues related to race, gender, and sexual orientation drive domestic politics. Foreign policy elites are from the same class that gave us the Great Awokening, and if your model of members of this class involves them being illogical and destructive fanatics on matters of identity (the correct model), you should assume that they take their attitudes with them when thinking about international affairs. Their assumptions, deepest convictions, and construction of reality shape the ways in which we discuss geopolitical issues, which most Americans have no firsthand experience with.

One may ask why Pussy Riot and the Russian gay propaganda law made such a big impression in the United States when other countries like Saudi Arabia have much worse records on human rights. There are some 71 countries right now that ban homosexual relations. Russia didn’t even do that, and there is apparently a gay scene in Moscow that looks a lot like it does anywhere else in Europe.

Russian opposition to LGBT triggers American elites more than anti-gay laws and practices elsewhere because Russia is a white nation that justifies its policies based on an appeal to Christian values. Unlike a country like Hungary, it actually matters for international politics. Remember, we’re talking about the same elite that can only get excited about random attacks on Asians if they can pretend it’s white people who are doing it, and can’t be bothered to care about black people shooting each other every day but will make excuses for those who burn cities down in response to a police officer shooting a criminal in the course of an arrest. Homophobic Muslims or Africans will never inspire all that much righteous fury in these people. The template of “white conservative Christians bad” is fundamental to their worldview, and this leads to not only hostility towards Putin, but also nations like Hungary and Poland, even if the latter are uneasily accepted as friends because they were grandfathered into NATO, the alliance that is of course aimed at Russia.

While populists like Tucker Carlson and Sohrab Ahmari are uninterested in antagonizing Russia, most Republicans in Congress and in the most influential think tanks are still stuck in the 1980s. Democrats will sometimes advocate for a less aggressive stance towards Iran and China, but it has become impossible for them to do so towards Russia, the homophobic white nation that gave us Trump and destroyed our democracy.

The rise of Orban and other right-wing populists in Europe has added to the hysteria. The way the media frames the issue, it’s a question of “democracy versus authoritarianism.” As I’ve pointed out before, this framing is mostly nonsense. See this New York Times article I recently highlighted, where it appears that biased media is a sign of authoritarianism, but only when that bias is towards supporting conservatives.

Conveniently, this article on the rise of authoritarianism in Eastern Europe has no mention of Ukraine, which with a score of 60, is even less of a “democracy” than Hungary (69), Serbia (64), or Poland (82), according to Freedom House. Such democracy ranking algorithms are stupid, but when even Freedom House can’t pretend Ukraine is a democracy, it tells you something about the state of that country.

Once you understand that American politics is motivated by some combination of interest group lobbying and culture war resentments, the hostility towards Russia begins to make more sense. It really is about the “rules based international order,” but that doesn’t actually mean following the fundamentals of international law like "don’t invade other countries or interfere in their domestic politics.”

If that’s what it was about, one might effectively respond that the US has in recent decades tried to overthrow more countries than everyone else in the world put together. Foreign policy elites ignore anti-interventionists who point out this fact, just as how members of their class ignore those who point out that Hungary arrests fewer people for speech than France does, or that if you really care about “black lives” you should be more concerned about the recent historically unprecedented increase in murder than police shootings, which are statistically rare.

Brexit, Trump, and the rise of Orban and other right-wing populists in Europe have helped solidify a narrative in which Russian hackers and influence operations are behind everything liberal elites find distasteful, from opposition to Syrian refugees to bans on Critical Race Theory. Here’s a website laying out all the things Russia has been accused of “weaponizing” in the media, including dolphins, federalism, and the weather. The details of debates surrounding the wisdom of NATO expansion and whether Ukraine actually matters to the United States are lost in the larger story, as emotional denunciations of Putin as the source of all anti-democratic activity drives attitudes and policies. Inconvenient facts are ignored because it’s not really about “democracy,” “international law,” or any of the other words they use to obscure the fact that it’s culture wars all the way down.

So What Will Happen in Ukraine?

Once we step aside from culture war resentments and focus on the hard realities of geopolitics, it is clear that Russia will eventually get its way because it cares more about Ukraine than the US does, and has the ability to threaten or use military force to get what it wants. When resolve and capabilities line up on the same side, that side is going to win. And the reason that Americans don’t care about Ukraine is that Ukraine objectively does not matter to the US. All the sophistry in the world coming from MSNBC hosts, ex-generals on the payrolls of defense contractors, and think tank analysts can’t change people’s perceptions here.

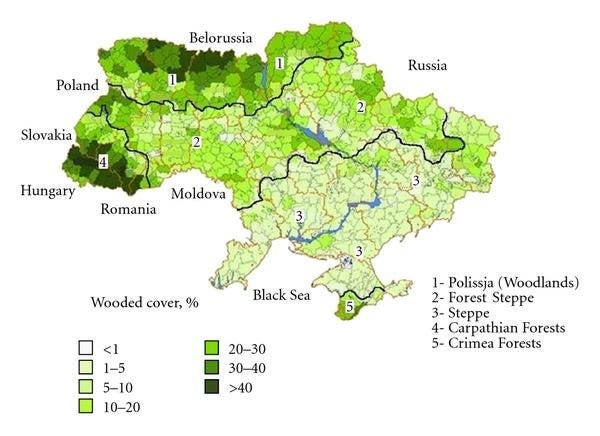

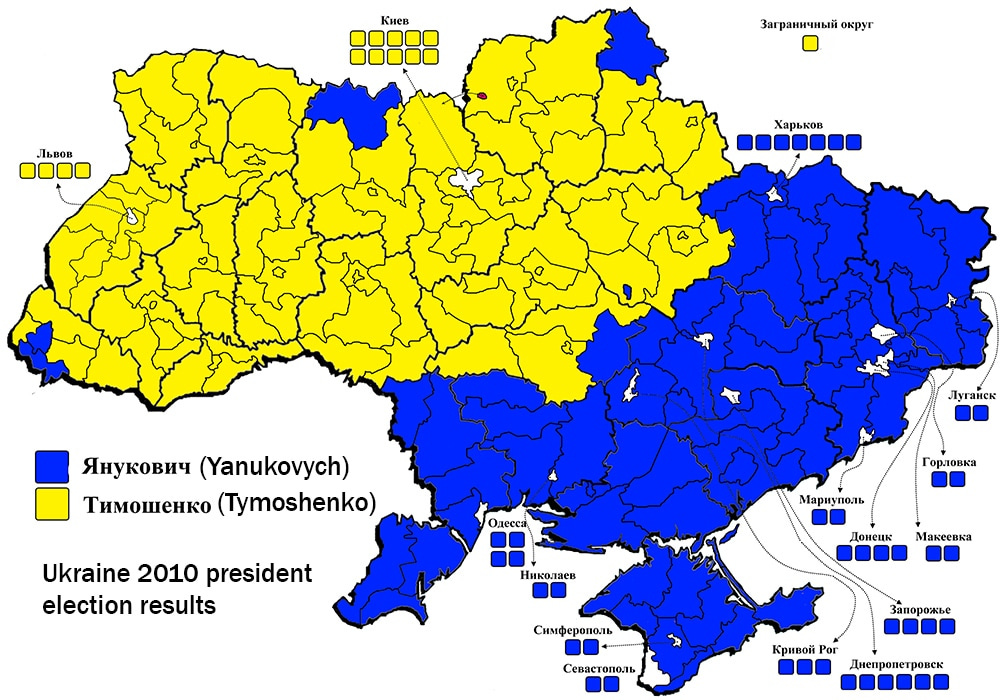

The only questions now are how far Putin will go, and how tough American sanctions will be. Washington is now deluding itself into believing that it can help facilitate an insurgency in Ukraine. This will not happen. One of the best predictors of insurgency is having the kinds of terrain that governments cannot reach, like swamps, forests and mountains. Ukraine is the heart of the great Eurasian steppe. It has some forests in the northwest and the Eastern Carpathians in the southwest, but Russia is likely to at most occupy the East and center of the country, where there are more Russian speakers, and give itself final say over whatever new government forms in Kiev. The two maps below show the percentage of Ukraine covered in forest by region, and that country’s presidential election outcome in 2010.

Source

Source

In the second map, blue represents support for Yanukovych (pro-Russia), while yellow is support for Tymoshenko (pro-West). As you can see, the most Russian areas are those with terrain least conducive towards fighting an insurgency. So Russia will have overwhelming military power in an area with a great deal of popular support on terrain that will make life for any rebels extremely difficult. Its army would be wise to basically leave a chaotic rump Ukraine in the West to its own devices.

Even setting aside the geography of the country, there is no instance I’m aware of in which a country or region with a total fertility rate below replacement has fought a serious insurgency. Once you’re the kind of people who can’t inconvenience yourselves enough to have kids, you are not going to risk your lives for a political ideal. When the US invaded Afghanistan and Iraq, their total fertility rates were 7.4 and 4.7, respectively. Chechnya, where Russia has faced insurgencies in recent decades, experienced a population boom after the collapse of the Soviet Union and was still well above replacement with a TFR of 2.6 in 2020, down from 3.4 in 2009, when the last Chechen war ended. Ukraine is at 1.2. We see numbers like this and don’t stop to appreciate the wide chasm that separates the spiritual lives of nations where the average person has 1 kid from those with 3 or more, much less 6 or 7, each.

On fertility, Russia isn’t that much better than Ukraine, but it’s got the tanks and a powerful air force, and the side that wants to fight a guerrilla war has to be the one that is willing to take a much larger number of casualties. There’s a consistent pattern of history where there’s a connection between making life and being willing to sacrifice it. This, by the way, is also why Hong Kong was easily pacified when China started clamping down, and why Taiwan will fold and not fight an insurgency if it ever comes down to it.

A weakness of the American empire is that it promotes ideals few are willing to fight and die for. The US faced vicious insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan because religion and nationalism are more powerful motivating forces than a concern with the western definition of “democracy,” and Iraq was only pacified through Shia religious militias with ties to Iran. In Ukraine, the American establishment has been embarrassed by the reality that neo-Nazis and nationalist organizations were instrumental in overthrowing Yanukovych and have helped form the new regime. It likewise wasn’t an accident that the US had to rely on religious fundamentalists to fight the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the 1980s. Even within the United States, liberal elites argue that they’re bringing women’s rights to backwards cultures while wringing their hands about the fact that Americans who actually fight our wars tend to be sympathetic towards “right-wing extremism.” This is the most overlooked contradiction of the American empire; you can bomb and drone those who resist, but Washington finds itself less effective the more it needs to rely on ground forces that are willing to make sacrifices for its ideals.

Again, There is No “Grand Strategy”

We know what the Russians want. They have made clear, openly and consistently, that they do not want NATO to keep expanding. When it became apparent in December that an invasion was on the table, the US started a diplomatic process that has involved trying to work out concessions on other things, while refusing to take NATO membership for Ukraine off the table.

Some have argued that there are currently no plans to bring Ukraine into NATO anyway, so there is no harm in just saying so if it might help avoid a war. This analysis is incomplete; the US foreign policy establishment believes that every country in Europe should eventually be part of the EU and NATO, and none should be allowed to get close to Russia or adopt a “nondemocratic” form of government, with “democracy” again being defined as making internal decisions that reflect the policy outcomes that State Department officials wish a Democratic president would implement at home. As Adam Tooze has shown in his excellent essay, Ukraine itself is lobbying hard for NATO membership, as is NATO itself. Putin understands that eventually, when Russia is weaker or has a president who is less willing to use force and economic coercion to get his way, the American establishment will take advantage of whatever opportunity it has to move history along.

It is still true that if Russia invades and turns Ukraine into a failed or subservient state, NATO membership is off the table anyway. So, again, why not just make the guarantee and avoid war? If the US had something called a “grand strategy” that reflected its more tangible geopolitical interests rather than policies determined by the prejudices and interests of a certain class, this is exactly what it would do.

But I wrote a book called Public Choice Theory and the Illusion of Grand Strategy for a reason. I don’t think Biden could make a deal if he wanted to. At various points in his career, Biden has shown a willingness to push back on the more insane suggestions of the foreign policy establishment, namely when it came to Libya and Afghanistan. His final withdrawal from the latter was one of the most courageous acts by a president most of us will ever see. But I don’t think he can grant concessions to Putin and survive. Biden would be eaten alive by the foreign policy establishment, the media, and Congress, uniting Republicans in opposition to him and splitting Democrats.

Even right-wing populists skeptical of defending Ukraine are bound to get more excited about tearing down Biden than about what the US actually does in Eastern Europe, as was demonstrated by their attacks on the Afghanistan withdrawal that they all had supported when Trump was in office.

If Russia invades, we will likely see sanctions, which are generally ineffective, but allow Washington to act as if it is “doing something.” The Russian economy might suffer, but sanctions are a double-edged sword and will push Moscow closer towards Beijing, which Washington claims not to want, but seems determined to do anyway. This would be something American elites would consider carefully if they had a grand strategy, but they don’t, and the US will continue down the self-defeating path of alienating both of the other two superpowers. Few appreciate the connection between ideologically-driven incompetence at home and abroad.