History Learner

Well-known member

On another website, a discussion has been fostered concerning Erich von Manstein's strategic thoughts on Italy in 1943/1944, as detailed by Benoit Lemay's Erich von Manstein: Hitler's Master Strategist. Basically, Manstein was in favor of abandoning much of Italy to Allied occupation, a view Rommel had shared in 1943 before being transferred to France, wherein the Germans would form a much shorter defensive line anchored along the easily defended Alps, allowing for the mobile units of Army Group C to be pulled out of Italy and used elsewhere. There was a lot of questioning over the cost/benefits of such a decision, as OTL Field Marshall Kesselring was able to mount a very successful defense of Italy, keeping much of its industry and labor in Axis hands while making the Allies pay a very heavy toll to conquer the peninsula. Personally, however, I am convinced Rommel and von Manstein were correct in their views, especially in 1944.

Looking at Army Group C's OOB in April/May of 1944, Armeegruppe von Zangen (LXXV Army Corps, Corps Witthöft, and Corps Kübler) could be left to guard the Alp passes as well as the Ljubljana Gap effectively. Given the terrain, logistics and the quality of the German forces, it would be impossible for the Anglo-Americans to breakthrough them; if there is any concern, Korpsgruppe Hauck could be detached from the 10th Army. Honestly though, given the need to extend their logistics across half of Italy, I doubt the Allies would even be in a position to launch an offensive until the the Spring/Summer of 1945. So, this frees up the German Army Group Reserve, 14th Army (I Parachute Corps and LXXVI Panzer Corps), and 10th Army (XIV Panzer Corps and LI Mountain Corps, if Korpsgruppe Hauck isn't detached, that too).

So, what does this all mean?

First, from the Allied perspective, they are going to need to garrison Italy heavily both because of all the ex-Fascists running around (Especially any RSI partisans) but also just in case the Germans emerge from the Alps into the Po Valley again at the first opportunity. Likewise, the severe shipping constraints means there isn't any real way to use them in OVERLORD or in ANVIL; once those operations are completed, they could shift forces through the French Alps but that will not be of much help given the severe logistical issues that crippled Allied Armies in the Fall of 1944. Southern French ports, for example, were already strained supporting the FFI, 6th U.S. Army Group and 3rd U.S. Army Group; adding more would not help matters. How about operations in the Balkans? In theory possible, but really bad in a political sense:

From Mark Stoler's Allies and Adversaries, Page 110-112. How about the Germans? From Lost in the Mud: The (Nearly) Forgotten Collapse of the German Army in the Western Ukraine, March and April 1944 by Gregory Liedtke, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies:

The Germans can also use this reserve effectively in the East:

So the formation and transfer eastwards of the reserve allows the Germans to avoid the destruction of roughly half (24 of the 50) divisions they lost IOTL, as well as anchor their Southern line along the Carpathians in the heavily fortified FNB line, while continuing Romanian oil shipments. I'm making the assumption that, without the destruction of 6th Army and the failure of Normandy, the Romanian coup can be avoided or pre-empted at the least. Perhaps equally important is that there is now more than enough additional formations to achieve a riposte similar to what von Manstein did at Third Kharkov in front of Warsaw:

From GERMANY AND THE SECOND WORLD WAR, Volume VIII: The Eastern Front 1943–1944 by Karl-Heinz Frieser, pg 569 onward:

With the additional firepower, Model should be able to encircle and destroy several formations of 1st Belorussian Front. In effect, you've replayed Early 1943 (~25 Divisions destroyed, Soviets regain territory but then the Germans revive and deliver a punch to the face) in 1944.

Looking at Army Group C's OOB in April/May of 1944, Armeegruppe von Zangen (LXXV Army Corps, Corps Witthöft, and Corps Kübler) could be left to guard the Alp passes as well as the Ljubljana Gap effectively. Given the terrain, logistics and the quality of the German forces, it would be impossible for the Anglo-Americans to breakthrough them; if there is any concern, Korpsgruppe Hauck could be detached from the 10th Army. Honestly though, given the need to extend their logistics across half of Italy, I doubt the Allies would even be in a position to launch an offensive until the the Spring/Summer of 1945. So, this frees up the German Army Group Reserve, 14th Army (I Parachute Corps and LXXVI Panzer Corps), and 10th Army (XIV Panzer Corps and LI Mountain Corps, if Korpsgruppe Hauck isn't detached, that too).

So, what does this all mean?

First, from the Allied perspective, they are going to need to garrison Italy heavily both because of all the ex-Fascists running around (Especially any RSI partisans) but also just in case the Germans emerge from the Alps into the Po Valley again at the first opportunity. Likewise, the severe shipping constraints means there isn't any real way to use them in OVERLORD or in ANVIL; once those operations are completed, they could shift forces through the French Alps but that will not be of much help given the severe logistical issues that crippled Allied Armies in the Fall of 1944. Southern French ports, for example, were already strained supporting the FFI, 6th U.S. Army Group and 3rd U.S. Army Group; adding more would not help matters. How about operations in the Balkans? In theory possible, but really bad in a political sense:

The problems with this strategy, according to the jssc, were both military and political. Eastern Mediterranean operations would require previously committed U.S. naval support, Turkish belligerency the jssc rated an overall liability rather than an asset, and offensives at the end of long and tenuous supply lines in an area so mountainous and remote from the center of German power as to be indecisive and invite stalemate or defeat. Moreover, such operations were based on the assumption that indirect campaigns in the Mediterranean against Germany’s satellites, combined with blockade, bombing, and guerrilla operations, could force a German collapse. Dubious under the best of circumstances, this assumption ignored the fact that an approach relegating to the Soviet Union the brutal task of fighting the bulk of the Wehrmacht while London reaped political benefits in the eastern Mediterranean and Balkans, an area of historic Anglo-Russian rivalry, might so arouse Russia’s anger and suspicion as to make it ‘‘more susceptible’’ to German peace feelers— especially ones which would grant Moscow its centuries old desire to control the Dardanelles.

The resulting separate peace would leave Germany undefeated and dominant in Central and Western Europe and would make Allied victory impossible.31 Even if such an appalling scenario did not develop, a Mediterranean strategy would involve the use of American forces to achieve British political ends. More threatening than the nationalistic insult involved in this perceived repetition of the attempted World War I manipulation of U.S. forces, Britain’s approach would negatively affect America’s military position and national policies in the Far East and, with them, Washington’s ability to pursue a Europe-first strategy in the future. The essential problem was that the time-consuming and indecisive Mediterranean approach would delay vital operations against Japan and, in the process, wreak havoc with America’s military position, its interests in the Far East, and public support for a global war effort. Even before Casablanca the jssc had concluded in this regard that the ‘‘basic difference’’ between U.S. and British strategy was not over the appropriate follow-up to torch, as London had claimed, but over the ‘‘relation of the war in the Pacific to the war as a whole.’’ 32

From Mark Stoler's Allies and Adversaries, Page 110-112. How about the Germans? From Lost in the Mud: The (Nearly) Forgotten Collapse of the German Army in the Western Ukraine, March and April 1944 by Gregory Liedtke, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies:

The need to reassign resources in the wake of the second stage of the Dnieper-Carpathian Operation also proved deleterious to the Germans’ prospects of successfully defending France. The withdrawal of two panzer and one infantry divisions, one heavy tank battalion, and two assault gun brigades meant that OB West (High Command of the German Army in the West, or Oberbefehlshaber West) was deprived of a total of 363 tanks, assault guns, and self-propelled anti-tank guns on 6 June 1944.72 Although the II. SS-Panzerkorps with the 9. SS-Panzer and 10. SS-Panzer Divisions were ordered back to France on 12 June, Allied air interdiction and damage to the French railway net delayed their arrival at the invasion front until 29 June. While their commitment at this point ended the British Operation Epsom (26–30 June), it also meant that German hopes for launching a concerted effort to wipe out the British portion of the Allied bridgehead were stillborn; henceforth these two divisions were fully preoccupied with simply trying to contain the Allied lodgement.73 One can only speculate as to the possible consequences had the II. SS-Panzerkorps already been stationed in France on 6 June. However, with its two divisions possessing most of their required number of motor vehicles and hence a high degree of mobility, and since all the other fully operational panzer divisions in France were committed almost immediately, it seems likely that the II. SS-Panzerkorps would also have been employed against the Allied landings at a very early stage. While the early deployment of an additional two panzer divisions with 245 tanks and assault guns may not have sufficed to wipe out any of the Allied beachheads, it would nonetheless have represented a major reinforcement.74 At the very least, the German containment of the landings would have congealed far sooner, and, in turn, German defense lines would have become even more formidable. Although the eventual outcome of the campaign would probably have remained the same, for the Allies, breeching these defences would have entailed significantly higher costs of time and blood. With the British and Canadian armies already experiencing dire shortages of trained infantry replacements during the campaign, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill worried that fighting in Normandy was degenerating into positional warfare reminiscent of the Great War, the situation for the Allies could have been far worse.75

The Germans can also use this reserve effectively in the East:

Under the actual circumstances faced by Heeresgruppe Mitte, even the speedy arrival of the strategic reserve may not have prevented disaster, but it may at least have reduced its scale and subsequent impact. A rapid forward deployment could have permitted the Germans to establish blocking positions further east than was in fact the case, resulting in the interception and wearing-down of the leading Soviet tank units at an earlier stage of the battle. In turn, this would have increased the likelihood of rescuing the large numbers of German troops that had been trapped within a series of isolated, wandering pockets. In this regard it is worth noting that small elements of the 12. Panzer Division alone, which began to arrive on 27 June, did in fact manage to rescue 15,000–20,000 men of the 9. Armee who had been surrounded in the area around the city of Bobruisk.79

Any lessening in the scale of the German defeat during Operation Bagration would also have produced a corresponding reduction in the urgency to shift resources from other sections of the Ostfront, leaving them stronger and far more capable of dealing with the Soviet attacks staged in their sectors. Although these would probably still have resulted in Soviet victories, Germany’s short-lived strategic reserve had the potential to keep these defeats from becoming outright catastrophes. By most accounts, the Lvov-Sandomierz Offensive already involved very heavy fighting during which the Soviets lost 289,296 men (representing 29 percent of their original force) and 1,269 tanks; had it retained a few of the formations it was forced to relinquish, Heeresgruppe Nordukraine would have posed an even greater challenge to the Red Army and may even have been strong enough to rescue its five divisions trapped around the city of Brody.80 Similarly, during the Jassy-Kishinev Offensive, the six panzer divisions given up by Heeresgruppe Südukraine would probably have been able to contain, and at the very least slow, the Soviet advance, thereby preventing the encirclement and annihilation of 18 German divisions. Without the destruction of over 50 of the 150 German divisions deployed on the Eastern Front in June 1944 during a series of pocket battles that summer, the westward advance of the Red Army would likely have taken far longer and cost far more lives than it did.

So the formation and transfer eastwards of the reserve allows the Germans to avoid the destruction of roughly half (24 of the 50) divisions they lost IOTL, as well as anchor their Southern line along the Carpathians in the heavily fortified FNB line, while continuing Romanian oil shipments. I'm making the assumption that, without the destruction of 6th Army and the failure of Normandy, the Romanian coup can be avoided or pre-empted at the least. Perhaps equally important is that there is now more than enough additional formations to achieve a riposte similar to what von Manstein did at Third Kharkov in front of Warsaw:

From GERMANY AND THE SECOND WORLD WAR, Volume VIII: The Eastern Front 1943–1944 by Karl-Heinz Frieser, pg 569 onward:

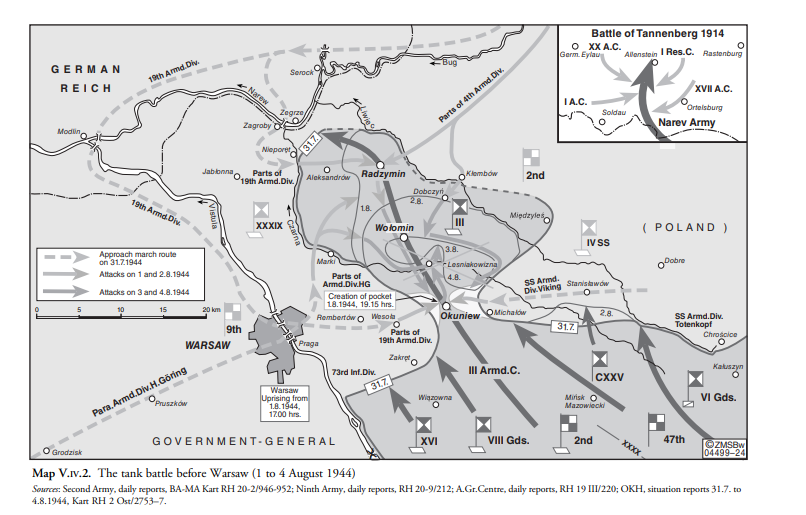

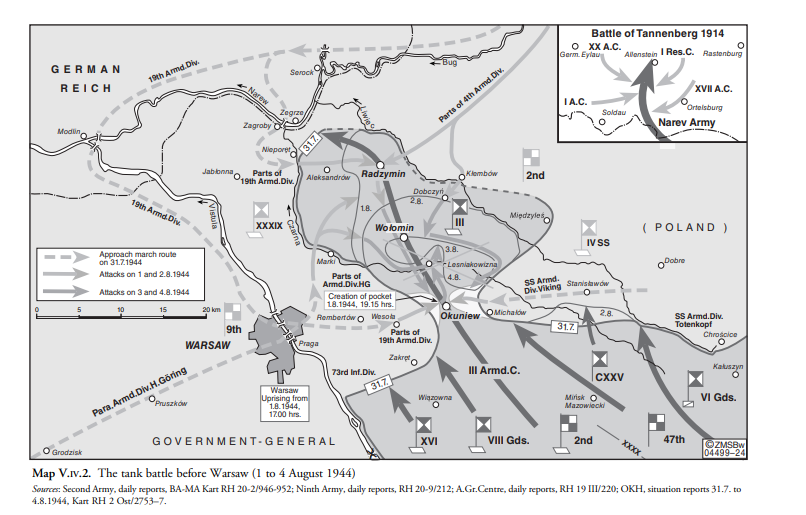

What now followed was a complete surprise. As if from nowhere, four German armoured divisions launched a sudden concentric attack on the area to the east of Warsaw, and the Soviet armoured units which had thrust forward in a preliminary attack were caught in the trap. The situation of Army Group Centre in July 1944 was similar to that of Army Group South on the Donets in February 1943, when the southern wing of the eastern front was threatened with encirclement and a ‘super-Stalingrad’. On that occasion Manstein had gained an armoured army as a mobile reserve by shortening the front, and had deployed it in a counter-blow after a wide-ranging castling movement.174 Exactly the same situation repeated itself in the summer of 1944 before Warsaw, although this time everything went much faster. Model had no time left to argue with Hitler for operational freedom of action. He simply took it for granted. In the given crisis, he had no alternative but to scrap Hitler’s rigid principle of linear defence and, like Manstein, pursue free combat in the rear. Model too took remarkably bold risks, withdrawing three armoured divisions from his army group’s shaky front for a counter-attack, which could only be done by yielding territory. In addition, Armoured Paratroop Division ‘Hermann Göring’ had just arrived in Warsaw. Together, these four armoured divisions possessed 223 tanks, plus 54 assault guns and tank destroyers. Those figures are purely theoretical, however, since the divisions in question did not arrive all at the same time but one after the other, and sometimes had to be withdrawn again at the height of the battle in order to ‘put a fire out’ at other places on the front. On the other side, 2nd Armoured Army had around 800 tanks and assault guns, although an unknown number had been lost in the meantime. The initial armoured strength of the Germans divisions on 2 August was as follows:175

• 19th Armoured Division: 26 Panzer IVs, 26 Panzer Vs, 18 light tank destroyers;

• Armoured Paratroop Division ‘Hermann Göring’: 35 Panzer IVs, 5 Panzer Vs, 23 Panzerjäger IVs;

• SS Armoured Division ‘Viking’: 8 Panzer IVs, 45 Panzer Vs, 13 assault guns;

• 4th Armoured Division: 40 Panzer IVs, 38 Panzer Vs.

According to Model’s operational plan, the first phase was to be a pincer attack on Okuniew to cut off the rear of the Soviet III Armoured Corps, which had advanced far to the north. The second phase was to be a concentrated attack by the four armoured divisions to destroy the units of the encircled Soviet corps. After that, the plan was to attack VIII Guards Armoured Corps, and finally XVI Armoured Corps. The assembly phase was the most complicated, however, since the four armoured divisions were located in completely different front sectors, from which they had to be withdrawn. Once that was done, they were to be shifted in a castling manoeuvre to the area east of Warsaw, and then to attack simultaneously from the four points of the compass. Given the far greater strength of the enemy, the right troops had to be concentrated in the right place at exactly the right time. The encirclement manoeuvre was extremely difficult to coordinate at operational level. Owing to the rapid course of events, tactical implementation could be carried out successfully only by officers trained in mission-type command. Knowing how much depended on the success of the operation, Field Marshal Model led the attack himself, leading his troops from the front.

At first only Armoured Paratroop Division ‘Hermann Göring’ was available, having just arrived in Warsaw from Italy. Although the bulk of the division was temporarily classified as ‘inoperational’, 176 on 28 and 29 July its few already available tanks were able, together with 73rd Infantry Division, to prevent the Warsaw suburb of Praga from being taken in short order by the advance troops of the Soviet 2nd Armoured Army. In the meantime, 19th Armoured Division had been withdrawn from its sector of the front at Białystok. Its first units arrived on 29 July, just in time to stop the Soviet tanks a little way short of the important Narew bridge at Zegzre. In a combined pincer attack, SS Armoured Division ‘Viking’ and 4th Armoured Division had just stopped the enemy forces which had broken through at Kleszczele. Now they too were hastily withdrawn from the front and reached the new deployment zone on 31 July and 2 August respectively.

The tank battle before Warsaw began on 1 August with a pincer attack on Okuniew. The spearheads of a combat group of 19th Armoured Division attacking from the west, and SS Armoured Division ‘Viking’ from the east, met to the north of Okuniew at 19.15, thereby cutting off the Soviet III Armoured Corps, which had advanced as far north as Radzymin. The attack by 4th Armoured Division, which had just arrived in the area, and by parts of 19th Armoured Division, was led by Field Marshal Model in person. The tank battle reached its climax on 3 August, when the Soviet III Armoured Corps was tightly concentrated in the area of Wołomin. The four German armoured divisions attacked concentrically from four directions: 4th Armoured Division from the north-east, SS Armoured Division ‘Viking’ from the south-east, Armoured Paratroop Division ‘Hermann Göring’ from the south-west, and 19th Armoured Division from the north-west. That day most of the Soviet units in the Wołomin area were destroyed, and the noise of the battle could be heard as far away as the centre of Warsaw. The next day, 4 August, the remaining sections of the Soviet 2nd Armoured Army were attacked, together with 47th Army, which had rushed to its assistance. The fighting was concentrated on Okuniew, where the Soviet VIII Guards Armoured Corps had taken up position. The plan had been to enclose and destroy that major formation too, but more bad news had since arrived from other sectors of the front. That same day 19th Armoured Division had to be withdrawn, and the following day it was the turn of Armoured Paratroop Division ‘Hermann Göring’. One after the other, the two divisions set off round the contested city of Warsaw towards Magnuszew to attack the Soviet bridgehead west of the Vistula, where 8th Guards Army, supported by 1st Polish Army and strong armoured forces, was trying to enlarge the bridgehead. In the evening of 4 August the German units at Okuniew went back on the defensive. The purpose of the operation—to prevent the enemy from advancing into the area east of Warsaw by means of ‘offensive defence’—had been achieved.177

With the additional firepower, Model should be able to encircle and destroy several formations of 1st Belorussian Front. In effect, you've replayed Early 1943 (~25 Divisions destroyed, Soviets regain territory but then the Germans revive and deliver a punch to the face) in 1944.