When 725 dawned, so did the reign of a new Emperor over the Roman world – Aloysius II, aged 34 as of his coronation as the third Holy Roman Emperor. Already a proven war leader by this time, Aloysius had cultivated a reputation not only for martial competence and valor but also for honor: fair in his dealings with prince and pauper alike, forthright and just, merciful to vanquished enemies like the Pelagian Britons but insistent that they change their erroneous ways, and not inclined to collective punishment (he did after all restrain the Africans from simply killing every Jew in their kingdom for the treachery of the elders of Lepcés Magna) but still capable of harshly judging and punishing individuals for their crimes (as Malcor de Gadé, or rather his ashes, can attest). The new

Augustus was also a reasonably learned man, his father Constantine the Wise having worked hard to personally educate him in the classics, religion and rulership from his childhood in Gaul. But where Constantine had a tendency to get too deeply wrapped up in intellectual matters, Aloysius was a more practical man in the vein of his grandfather, to whom knowledge was a tool rather than an end in and of itself – his longest-lasting and most influential work was a treatise on the

habiti or basic virtues, all of which he tied to the four cardinal virtues passed from the pagan philosophers of old to the early Church Fathers such as Ambrose & Augustine, which were supposed to govern the conduct of the early knights of his day – and who would rather find a worldly application for his scholarly background than debate how many angels could dance on the head of a pin all day.

In any case, the manner in which Aloysius II's reign began left him with no time to luxuriously engage in intellectual pursuits. After arranging a betrothal between his thirteen-year-old eldest son, the new

Caesar Leo, and the English king Æthelstan's daughter Æthelflæd to demonstrate not only his respect for the longstanding Anglo-Roman alliance but also a commitment to keeping Britain (the island, not merely the kingdom) Roman this time, he set out for the continent where the machinations of Anastasios of Thessalonica had flared up into rebellion, taking with him 10,000 legionaries and leaving the other 20,000 under trusted dukes and counts to support Artur V in establishing his authority over Britannia. While the Roman Senate quickly hailed Aloysius as the new

Augustus without a fuss, the Constantinopolitan Senate was mired in much more confusion and difficulty, as the Reversionists pushed hard for the candidacy of the Macedonian magnate Ioannes Lachanodrakon; those Senators they could not bribe with gold or promises of high office, they tried to turn against the latest Aloysian royal to demand their fealty with anti-Council of Miletus religious appeals or arguments for Eastern Roman independence, claiming that the Aloysians would always be too distracted with projects in the Occident to focus on tasks like recovering Egypt & the sweeping conquests of Sabbatius.

In the end, Lachanodrakon and Anastasios' efforts were for naught, as the Trithyrii relatives of the Emperor were able to rally two-thirds of the august chamber to hail Aloysius as

Augustus and Patriarch Nicholas of Constantinople did the same. Undeterred, the rebellious Macedonian nobility and Reversionist diehards acclaimed Lachanodrakon as Emperor John I in Pella anyway, driven mostly by fear (stoked by Anastasios) that Aloysius II would punish them for having taken such a public stand against him in an effort to steal an entire half of his birthright away. Such fears were well-founded, but the usually merciful Aloysius was not likely to have issued the death penalty (or at least, not for most of them) until they actually rose up in arms against him. At the time this news reached the legitimate

Augustus, he had just reached Rome for his formal acclamation by the Roman Senate and coronation by the extremely aged Pope Vitalian: but having been informed that the rebellion was limited to northern Macedonia, he trusted his cousin Demetrius Trithyrius would make short work of the rebels.

Flavius Aloysius Augustus Secundus 'Britannicus', aged 34 at the time of his coronation. Though neither as martially gifted as his glorious grandfather nor as renowned a scholar as his wise father, the second Aloysius also lacked their deficiencies of character and would be celebrated in history as 'Europe's first knight' for his virtues, chiefly a strong sense of honor which tempered his still-considerable war-fighting ability.

In Aloysius' defense he had no real reason to assume otherwise, as Demetrius did immediately take command of the

exercitus of Thessalonica and led it against the insurgents, who were so frightened by the numbers they faced that they fled Pella without a fight. However, while trying to coordinate the envelopment of the remaining rebels in the Dardanian mountains to the north with Serb federate forces, the Praetorian Prefect of the East was killed in an audacious night raid led by Lachanodrakon: apparently he had been operating under the belief that the rebels would never do something so obviously foolhardy as actually come at his overwhelmingly superior forces themselves, and paid for it with his life. Lachanadrakon and Bishop Anastasios took advantage of the ensuing confusion to bribe several of the Danubian legions, allowing them to defeat the demoralized and headless Aloysian loyalists in the Battle of Estipeon[1], after which they turned around to put the Serbs of

Vozhd Ninoslav to flight at the Battle of Tetovo (then still known to the Greeks & Romans as 'Oaeneum').

The rebels next moved back toward Thessalonica, using their extraordinarily lucky back-to-back victories to sway the garrison & populace into opening their gates and hailing Ioannes Lachanadrakon as the Emperor of the East, while the loyalists of the Thessalonican imperial army fell back to Constantinople instead. These developments had come as a rude surprise to Aloysius himself, who had been properly crowned and just finished confirming Venexia's[2] charter privileges – the port city having come a very long way over the centuries since the days when its main claim to fame was being the site of Emperor Romanus I's demise after his disastrous clash with Attila – when he heard the news. Now forced to address the Reversionist rebellion as an actual threat, Aloysius committed himself fully to crushing the traitors quickly (certainly with such speed that nobody else, like the Stilichians for example, may get any funny ideas, nor would the Muslims be encouraged to attack) and maneuvered to bring together both the Treverian and Antiochene

exerciti, the former backed by contributions from the Teutonic & Slavic federates and the latter by the loyal Anatolian Greeks, Bulgars, Caucasians & Arabs, so as to stomp Lachandrakon flat between them.

Ambush of Aloysius II's and Demetrius Trithyrius' loyal legions in the lead-up to the Battle of Estipeon by the rebels of Ioannes Lachanadrakon

While Aloysius II was moving to consolidate his rule at its very outset, his Khazar cousins were putting the first stages of their scheme against him into play. Bulan Khagan led the Khazar hordes against the Avars, who had been unable to pull out of the death spiral they'd flown into since Aloysius I shattered their ranks at the great siege of Constantinople and the Turkic elements then rose against their Rouran overlords decades prior. His impression that the Avars would not be a particularly difficult foe was proven right early on, as the Avars' own horde was indeed soundly defeated and their leader Toghan Khagan slain in the Battle of Tyras[3] on the Dniester – the first real battle of the Avar-Khazar war. While Toghan's son Balambär retreated into the Dacian mountains, Aloysius II made no move to assist the Avars, not only because he was busy with the Macedonian rebellion and because the Avars had been a thorn in Rome's side for two centuries but also because he had no reason at this time to doubt Bulan's intentions when the latter assured him that he just wanted to clean up a mutual threat for the benefit of both their empires. At this same time, Hashim and Nusrat al-Din had also noticed the disorder in Macedonia, and began to amass resources for another campaign against Syria & Palaestina in hopes of rivaling the successes of the former's Alid cousins and redeeming the main branch of the Hashemites in the eyes of their temporarily-chastened subjects.

The last significant development this year was in Britannia, where one of the two Pelagian delegates managed to make it back to Cambre in the guise of an Irishman (with which he had made it through the Irish colonies in the New World, but which also almost got him killed shortly after landing back in his homeland). The rebel leadership, still fighting a losing battle against the legions of Rome and Artur's partisans, was divided over how to respond to the news that while their own colony on the other side of the Atlantic still stood, actually getting there was certain to be a nightmarish process beset by the risk of dying from starvation, freezing, drowning or the axes and javelins of the Irish. One faction, initially led by Bishop Deué ('David') of Léogaré[4], insisted on carrying out the original plan no matter what obstacles lay in their way; comprised primarily of lower-ranking Pelagian clerics and laity filled with such zeal that they rejected any compromise with the Romans and could not countenance living under Ephesian rule no matter what, they would be known to historians as the 'Pilgrims'. The other faction, spearheaded by the higher ranks of the Pelagian clerical hierarchy and the nobility with not-inconsiderable lands & fortunes to lose, advocated negotiating with Artur & Aloysius II, accepting the Proclamation of Verúlamy and using the grace period of tolerance to build up an 'underground church', to which faithful Pelagians would retreat and continue to practice their true faith in secret once the Romans and their puppets inevitably retracted their tolerance. So-called the 'Remnants' and originally led by Bishop Merí ('Marius') of Magné[5], this faction remained behind even as the first Pilgrims loaded onto their boats to take their chances across the Atlantic.

As the Romans slowly but surely close in on their mountain holdfast in Cambre, Bishop Deué of Léogaré is counseled by Merí of Magné to stay in Britain rather than test his luck over the Atlantic

As soon as weather conditions permitted it, Aloysius sailed from Venexia to Dyrrhakhion[6] in the early months of 726 with his 10,000 legionaries and another 5,000-strong assortment of Slavic auxiliaries assembled over the winter. From the latter city he marched into Macedonia during the spring, while Lachanodrakon's rebels had tried and failed to capture Constantinople: having expected the Eastern Senate to crown him after his earlier victories, the usurper had instead found the city gates barred against him when he reached it and hadn't even begun to assail the outermost Anthemian Wall when the Antiochene

exercitus began to cross the Hellespont, forcing him to retreat in a hurry. The rebel army now found itself in danger of a much larger and more threatening double-envelopment, trapped between the approaching host of Aloysius II from the west and the Antiochene-Anatolian army from the east.

Lachanadrakon decided to throw everything he had into an engagement with the lawful Emperor, betting on his lucky streak still holding into the new year and hoping that he'd be able to kill the latter, after which surely the Orient would finally acknowledge the righteousness of his cause. The two armies met on the shore of Little Lake Brygeis[7], south of Damastion[8], as the imperial host was about to exit the Pindus mountain range; the usurper drew up his larger army of 20,000 to block Aloysius' passage, confident that his greater numbers and high-ground advantage would give him the victory. Undeterred, Aloysius formed his best and most heavily equipped soldiers (legionaries and federate auxiliaries both) into a dense offensive wedge and led it straight into the rebel center, tearing through their ranks with all the ease of a red-hot knife through butter. To his credit Lachanadrakon did not try to flee, instead actively seeking out the

Augustus in a frantic attempt to kill him and thereby reverse the tide of the battle; he got his desired duel, but did not last long against Aloysius, who then compelled the remainder of the rebel soldiers to surrender by presenting before them the sight of their pretender's head on a lance.

The sticky end of Ioannes Lachanadrakon, who however would be but the first of several Greek usurpers to challenge the Aloysians for control over the Roman East over the next few centuries

The Greek rebellion rapidly collapsed following the Battle of Lake Brygeis, as nearly all of Lachanadrakon's followers wasted little time in similarly throwing themselves as Aloysius' mercy save for a few recalcitrant Reversionist holdouts. Anastasios of Thessalonica was among them, but he was captured, defrocked and – after persistently refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the Council of Miletus despite having signed off on its canons – ultimately burned at the stake, both for heresy and for inciting the revolt in the first place. Aside from making a fiery example of the other rebel chief, Aloysius generally pursued a conciliatory approach of collecting fines and hostages from the vanquished; the legions which had defected to Lachanadrakon had their commanders demoted, imprisoned or executed, but the common ranks were not decimated (as they would have been in elder days) per the

Virtus Exerciti, just subjected to the originally post-decimation punishment of being made to bivouac outside of the army camps' fortifications and being promised the chance to redeem their honor by forming the front ranks in their next battles and the first wave in any siege. With all that out of the way, Aloysius proceeded to Constantinople to be formally acclaimed by the Eastern Senate and receive the blessing of Patriarch Nicholas; this mercifully short episode was the first source of unexpected difficulty he had to overcome in his reign, but it would not be the last, nor even remotely the worst. Fortunately, neither was it the first or last time the third Aloysian Emperor would bounce back from an initial spot of bad luck to subdue his enemies, either.

Immediately to the north of these events, Bulan Khagan continued to press the Avars hard, and further improved his position at the expense of Balambär Khagan's loyalists by swaying many Turks and Slavs alike to defect to him with promises of leniency, generosity & places of honor within the Khazar confederacy while threatening anyone who refused with extermination. Balambär planned to cross the Danube and ride into Roman territory, finding his situation untenable and hoping that either he would be able to negotiate the Avars' resettlement within the Empire as a new federate state or else conquer a new kingdom out of Roman Macedonia and Thrace, but Bulan moved with such speed that he had no time to carry this scheme out. At the Battle of the Naparis[9] the Avars suffered their final defeat and Balambär was killed, spelling an end to their Khaganate and the Khazars' acquisition of a Danubian border with the Holy Roman Empire; the Avars only managed to sour the victory by killing Bulan's eldest son Barjik Tarkhan, for which the Khagan ordered the annihilation of Balambär's clan in revenge. In order to keep up appearances and buy himself time to both digest his new conquests & strengthen his own army, Bulan prohibited raids over the Danube for the time being, in the process assuring Aloysius II of his continued friendship.

The equally sticky end of Balambär Khagan, last ruler of the Avars, amid Roman ruins near the River Naparis. Unlike the case with Greek rebellions, the Avars would never rise again after his downfall, closing the book on two centuries of turmoil along the Danube – or so Aloysius II hoped

On the other side of the world, the first parties of the Pilgrim faction of Pelagians began their arduous trip across the North Atlantic this year. They carried possessions with them in part to, where possible, bribe the Irishmen they encountered to not attack them; where this failed, they used weapons to defend themselves aboard their boats or in their camps in Paparia. Still the cold, hunger and Irish raids took its toll on their ranks, their only relief being that – as they got closer to the shores of Aloysiana – the Pelagians already there had done them the favor of recapturing the Isle de Sanctuaire in a surprise attack, wiping out the meager Irish garrison on the island (few were inclined to settle it when they still had plenty of room on Tír na Beannachtaí and Nova Hibernia) and building a new tower where their old one had once stood, thereby making the last leg of the voyage slightly less hellish. Meanwhile, the majority Remnant faction had entered into negotiations with Artur V's government, arranging a ceasefire and peace talks with the hope of securing not just a royal pardon but also the space and autonomy to begin setting up their underground church with minimal oversight on the part of the new ecclesiastical authorities.

727 was a fairly eventful year for the Aloysians, despite the empire-wide return to peace. After completing his progress toward Antioch and Jerusalem and looping back into Anatolia, in the process witnessing the Muslims in the east backing down for the time being when it became clear that the Greek rebellion had fizzled out (after all they had yet to rebuild their full strength after their latest

fitna, although Hashim & Nusrat al-Din did increase the weight of the

jizya on the shoulders of the Ephesian Christians in their domain), Aloysius II celebrated the wedding of his now fifteen-year-old heir Leo to the English princess Æthelflæd (a year his senior) and also arranged for the newlyweds' settlement in the court of his Frankish brother-in-law Childeric IV. Not only did this keep them close enough to Æthelflæd's family to visit them often and allow Leo to acquire practical experience at rulership in the controlled environment of Lutèce, but Childeric himself had failed to sire any children at all; Aloysius no doubt hoped to engineer his own son's eventual inheritance of the Frankish crown (as the closest relative of the incumbent king, Leo's uncle) ahead of the other, more distant Merovingian cadet branches, thereby absorbing Francia altogether and placing the entirety of Gaul back under direct imperial rule. Aloysius also gave Pontic-grown tea to King Æthelstan and the Raedwaldings as a wedding gift, marking the first occasion in recorded history that tea had made it to English shores.

The

Augustus next turned to religious matters. To honor the memory of his grandmother Helena and grant some visual representation to the Greek half of his empire, he added the Christogram IC|XC|NIKA ('Jesus Christ Conquers') to the blue-and-white

labarum of his dynasty. He also took advantage of this lull in hostilities, both with internal opponents and Islam, to call yet another ecumenical council with the intent of answering the questions which the bishops did not have enough time to deal with at Miletus years before; his father's lack of time to address these questions then contributed to the collapse of earlier efforts at a compromise with & negotiated annexation of the British high kingdom, and Aloysius hoped to avoid the same problem. Importantly, since this inevitably meant handling questions of sin and salvation, this would be the council where he intended on bringing British Christianity back into the fold and making it easier for orthodox missionaries to sway the Pelagians – without, of course, compromising core dogma (what happened with Semi-Pelagianism had proven that such an approach would fail anyway). For its site Aloysius chose Smyrna, one of the 'seven churches of Asia' addressed in the Book of Revelation which was situated north of both Ephesus and Miletus but still within the borders of Ionia, now emerging as a sort of miniature 'holy land' for the Christianity of the Holy Roman Empire after so many important church councils had taken place on its soil. It is from this point in history onward that the orthodox Christians are no longer referred to simply as 'Ephesians', but 'Ionians'.

The modified Aloysian labarum from 727 onward. By order of Aloysius II the Greek Christogram for 'Jesus Christ Conquers' now adorns this standard, both honoring the legacy of Helena Karbonopsina and lending it more of a Greek flair

After once more assembling the bishops of the Church, Aloysius opened the floor to ecclesiastical debates late in this year. On the agenda were questions of original sin and how it affected infants who did not survive to be baptized, salvation and predestination. Hostilities flared up immediately between the African bishops and the British Ionian delegation led by Íméri (Ambrosius) de Brévié[10] – a man chosen specifically because he had been jailed, tortured and nearly martyred by the heresiarch Malcor, had it not been for Aloysius' decisive victory at Métanton, and thus one whose commitment to Ionian orthodoxy was unimpeachable – who made it readily apparent that they brought a more inclusive Pelagian-influenced approach to all these issues, which stood completely at odds with the hardline Augustinian-derived thought of the Africans. Now this much, virtually everyone (including Aloysius II himself) had expected. What was less expected was the African Church's theological isolation, as the various positions which they staked out – that not only were all men tainted by original sin but also that unbaptized infants went to Hell, and that God predestined some men for salvation (even if, unlike the Donatists, they did not also believe that God predestined others to damnation) – were not supported by any of the other Sees of the Heptarchy, who found these stances far too extreme and possibly Donatist-tainted for their liking. Bishops from the Roman See to that of Babylon soon weighed in against the Africans, who locked ranks in response.

While presiding over the Council of Smyrna, Aloysius did push forward on some of his father's planned reforms while retreating from others. He committed to the legacy of Constantine VI's Senate reforms, finalizing the drafts of the plan to introduce barbarian princes from the federate kingdoms into that august chamber in exchange for conceding some legislative authority back to them and their leader, the

Princeps Senatus. It was the hope of Aloysius that if this new policy worked out, he could repeat it in the Orient by bringing Arab, Caucasian and Serbian (for after all their kingdom lay in the part of Illyricum traditionally assigned to the Eastern Empire) representatives into the Senate of Constantinople and thereby bind those outlying federate states closer to the Holy Roman Empire in much the same way. The new Emperor did advise the Roman See to once more allow priests to deliver their sermons in the vernacular of their homelands however, and to reform the standard pronunciation of Latin away from the manner of Cicero which was unpronunceable by virtually everyone outside of the old Senatorial elite and the uppermost echelons of the Western Church[11]: he simply did not share Constantine VI's interest in the subject of linguistics and thought trying to force a reversion to Classical Latin to be far, far more trouble than it was worth. In this measure Aloysius II was supported both by Pope Vitalian, though he was on his deathbed this year, and Vitalian's successor Boniface II (who, though still an Italian himself, made history as the first Pope elected with the input of non-Italian cardinals).

In China, the power and wealth of the Later Han was fast waxing and approaching its zenith under the successor of Zhongzong, Emperor Guangzong ('Bright Ancestor'). A more peaceable man than his father, the last Later Han Emperor to seek outward expansion (and who found the southernmost limit of Chinese power projection in his stalemate with Srivijaya), Guangzong was a patron of the arts, including poetry and even encyclopedias, and also a man interested in bringing China to ever loftier heights of material prosperity. He fully rebuilt commercial links with the Srivijayans and expanded maritime trade with partners in India & even Arabia, turning the port of Guangzhou into a metropolitan emporium hosting thriving communities of expatriate merchants from all backgrounds and following all sorts of creeds – Buddhist Srivijayans and Hunas, Hindu South Indians, Muslim Arabs and Persians, Christian Indo-Romans and Greeks, and so on. In turn, this heightened trade helped Caliph Hashim refill his coffers, cultivate an independent powerbase apart from Nusrat al-Din and the

ghilman, and turn Basra into a bustling economic center in addition to giving him ideas for the construction of a canal linking the Red Sea to the Nile (so as to further improve trade) in the future – Chinese silk, lacquer and porcelain were always in extremely high demand in the distant west after all. Technological changes which improved the Chinese people's quality of life, such as the popularization of toilet paper and dental fillings made from silver & tin, also emerged under his reign.

The Later Han soared to the apogee of their prosperity under the aptly-named Emperor Guangzong, engaging in lucrative trade with the outside world along both the overland & maritime Silk Roads and with a population swollen to around 75 million (with two-and-a-half million living in the capital of Luoyang, and other great cities such as Guangzhou boasting half- to one-million residents)

Elsewhere, under conditions that could not remotely be described as materially prosperous, Pelagian Pilgrims began to arrive in the New World in significant numbers. Even as battered as they were by attrition, they came to outnumber the original population of Porte-Réial, most of whom now had at least one Wilderman parent, not that this was overly difficult considering that there were only at best some 2,000 British settlers spread out over the entirety of their Aloysianan colony at its pre-Métanton height. Though they naturally still shared a common religion, tensions rapidly emerged between the original settlers' descendants and the newcomer exiles over just who should be running the show on the far side of the Atlantic without a

Ríodam whose legitimacy was unquestioned by both factions. Bishop Deué, who had lost his brother and the latter's entire family in the crossing, managed to cool tensions and arrange a truce before any of the more aggressive partisans on either side could escalate to violence, with the promise of setting up an equitable government representing the interests of both the locals and the newcomers at a 'Second Round Table' in just a few more years' time.

For Rome, 728 continued to be a year dominated by the debates at the Council of Smyrna, which suited Emperor Aloysius II just fine – he hoped to settle as many questions of doctrine as possible in this one sitting so that the Church would stand united and his heirs would not have to call another ecumenical council for at least another century or two. Tensions remained the highest between the Africans and the British: the latter, while professing belief in the Ionian conception of original sin (if they did not, they would still be Pelagians and have no place at this church council), also tried to articulate a belief in universal salvation – a position which won them support from, of all people, the Mesopotamian delegation friendliest to the teachings of the universalist Church Father Origen – as well as the primacy of good works in securing one's salvation, for engaging in works of charity and faith proved a commitment to living Christ's teachings; positions which no doubt had been inherited from the Pelagians, albeit modified to better fit the structure of Ionian dogma. These positions were anathema to those of the Africans, who fought to defend the concept that God justified men's salvation through His divine grace, and one could not 'earn' his way into Heaven with earthly works.

These soteriological debates rapidly spilled over into additional related questions such as the fate of unbaptized infants and whether a benevolent God would save all who live or consign at least some people to everlasting torment (or predestine some to one fate and others to the other), steadily ratcheting up the temperature in the basilica of Smyrna. The other episcopal delegations spent almost as much time trying to keep the Africans and Britons from strangling one another as they did arguing (albeit in a more moderate form) with the former. Certainly there were differences between the Roman and Constantinopolitan Sees on, for example, the extent of original sin (both agreed all men were tainted by sin since Adam & Eve, hence why none could be called perfect to this date save Jesus himself and also arguably Mary, but disagreed on whether all men also carried

guilt for original sin rather than simply having their nature inherently corrupted by it) but these paled to the vehement disagreement between Carthage and the British, or indeed, Carthage's extreme positions and their own milder ones.

At the fever pitch of these intense religious debates an exasperated Íméri de Brévié did dare to accuse the Africans of having become just as unforgiving, cruel and self-righteous as the Donatists they battled, and of interpreting God in the same way; what then does it profit them to finally destroy Donatism, if the cost of doing so was essentially becoming Donatists themselves? The outraged African bishops had to be physically held back from walking out on the council by the Emperor's paladins, and Aloysius personally intervened to talk them into staying. From here matters de-escalated somewhat, as the British delegation took a lower profile in the ongoing debates (perhaps not entirely by choice, Rome having leaned on them to keep their heads down after delivering a mortal insult like that to the Africans) while the African delegation was evidently stung a lot more deeply by the blow than they initially let on (perhaps De Brévié's words had rattled them so because they were worried it may have held a kernel of truth?). The

Augustus turned to the other six Heptarchic Sees, but especially Rome and Constantinople, to arrange compromises capable of binding his British 'prodigal son' and African 'elder son' back together in the Roman 'family' (and also reel the Africans back toward orthodoxy, as he'd heard enough to fear that they may be verging on heresy themselves).

The reincorporation of Britannia into the Holy Roman Empire and the presence of British bishops at the Council of Smyrna inevitably led to a reenactment of the Augustine-Pelagius debates from 300 years prior. Although this time, it was the Africans who were perceived to have taken their theological father's positions to extremes he would probably not have agreed with in his lifetime, and in any case the other Sees of the Heptarchy found both of them to be in error on at least some major points

The Emperor was not the dedicated academic that his father was, but he was sufficiently knowledgeable to know that the other sees' bishops were getting somewhere with the compromises they were building over the latter half of 728. Despite their differences over the extent of original sin, Rome and Constantinople both fundamentally agreed that it existed and that faith and good works were equally important in attaining salvation in spite of it: the Africans may be inclined to quote the Second Epistle to the Ephesians where salvation through faith is concerned, and the Britons fall back on the Epistle of James for similar yet opposite reasons, but to the Romans and Greeks these were not contradictory positions but two halves of a whole – one cannot be saved without faith, true faith manifests itself in good works, and faith without works was dead.

The eastern and southern-most bishops helped them finesse the understanding of good works as being products of human free will

working together with and assisted by the grace of God, not something which could only be produced by the will of God, since the latter necessarily removed human free will from the equation. Both were united against the concept of predestined salvation, believing it contradicted God's respect for human free will (and being unable to fit the square peg which was idea of a loving God into the circular hole of a God who would deny not only salvation itself, but the mere possibility of ever reaching it to any of His creations), as well as the idea of universal reconciliation, since if all could be saved regardless of belief then there was fundamentally no need for Christ to take human shape, issue his righteous teachings, die and be resurrected. By extension, the sacrament of baptism was still considered meaningful and necessary in order to be cleansed from sin's taint as an infant.

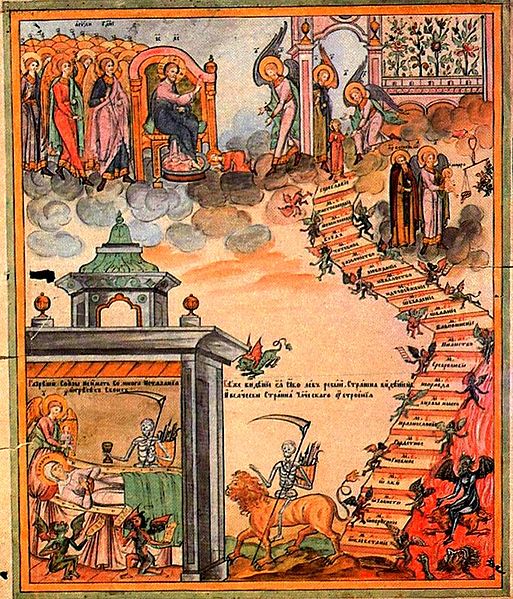

From the Greek East Aloysius II developed a keen interest in the concept of

telonia, or toll-houses in the sky which recently departed spirits had to pass through and argue their way past demons in order to reach Heaven[12]. It was not actually treated as doctrine by the See of Constantinople, merely a position grounded in Anatolian Christian folk tradition and advocated by some (but not all or even most) bishops, but to the Emperor it seemed like a good start toward the formulating of a true doctrine on an 'intermediate state' in the afterlife between Heaven and Hell, which he thought would make for an out-of-the-box but sensible compromise in regards to those who have died without having met the prerequisites agreed upon by all but actual Pelagians for salvation (that is, baptism – for unbaptized infants – and consistent belief in God – for virtuous pagans existing after Christ's Harrowing of Hell). Aloysius could not have known it at the time, for indeed it would take much longer than a singular church council or his own lifespan to fully develop the concept on which he'd started work, but he had set in motion the development of the much later Ionian understanding of Purgatory and Limbo.

Most prominently followed among the loyal Greeks of Anatolia, the concept of 'aerial toll-houses' provided the Aloysians and their partisans with fertile ground in which to lay the seeds – derived from Old Testament passages supporting the idea of helpful prayers & afterlife purification for the dead – that would one day grow into the doctrine of Purgatory, their answer to the questions of sin and the fate of the virtuous but unbaptized dead which stuck out as a major theological contention between Carthage & Britain

In this year, more Pilgrims undertook the harrowing journey to the New World, and were at this stage still not decisively obstructed by the Romans. In the reasoning of Aloysius II most would probably not survive the journey; it was better that such determined malcontents leave for someplace where the authorities wouldn't have to squander resources policing/suppressing them; he could essentially outsource the task of harassing the Pilgrims to the Irish for free; and in any case, between the persistent Muslim threat and the ongoing Council of Smyrna, he had much more important business to attend to anyway. Meanwhile in Britannia itself, the Remnant leadership was wrapping up negotiations for their terms of surrender.

The remaining rebels agreed to stand down, allow Ionian missionaries to operate and Ionian churches to be built in their fiefdoms, accept responsibility for any assaults/damage done to them respectively, and to not build new Pelagian churches to compete – they would only be allowed to maintain and practice at existing ones. In exchange Artur V agreed to pardon them, not to touch their hereditary titles and estates (although their continued commitment to Pelagianism excluded them from court and military involvement), and to assure them of the right to public practice of the Pelagian heresy under the terms of the Proclamation of Verúlamy. In essence, both parties got what they wanted: the Romans and Roman-aligned Pendragons put an end to the overt sectarian violence in Britannia (for now), while the Remnants bought themselves time to begin organizing their 'underground church'.

British Pelagians of the 'Remnant' faction hoped to set up the infrastructure to sustain an underground church of true believers once the Ionians grew weary of tolerating their presence, hearkening back to the days of the Early Church which endured Roman persecution. Of course, the problem was that not only did the British Ionian Christians claim the same legacy, but they could guess at such ulterior motives on the part of their enemies and would surely be...displeased to find their grace being taken advantage of

====================================================================================

[1] Astibus – Štip.

[2] Venice.

[3] Tiraspol.

[4] Leugarum – Loughor.

[5] Magnae Dobunnorum, or Magnis – Kenchester.

[6] Dyrrhachium – Durrës.

[7] Small Lake Prespa.

[8] Resen, North Macedonia.

[9] The Ialomița River.

[10] Durobrivae – Rochester, Kent.

[11] Essentially formalizing the shift from Classical to Ecclesiastical Latin, which was historically done in the late 8th/early 9th centuries through the Carolingian Renaissance.

[12] This is an actual Orthodox teaching of disputed canonicity even to this day, supported by some saints going back to Anthony the Great and Diadochos of Photiki, but challenged by others. It's the closest approximation the Orthodox have to the Catholic Purgatory (which is not a doctrine accepted by the Orthodox).